The First Republic In Nigeria And Its Collapse (1960-1966)

Nigeria became recognized as a Republic on the 1st of October, 1963, but this did not mark the beginning of Nigeria’s political journey as a Republican state. The first republic in Nigeria started on the 1st of October, 1960 upon the attainment of independence and ended on the 15th of January, 1966 during the first military coup d’état.

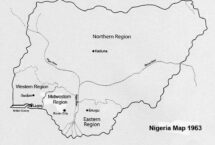

During independence, Nigeria had all the features of a democratic state and was seen by other African countries as a hope for democracy. Nigeria had a federal constitution that ensured adequate autonomy to three (later four) regions which were: Northern region, Eastern region and Western region; the country adopted and operated a parliamentary democracy that emphasized majority rule; the constitution included an elaborate bill of rights; and, unlike other African states that adopted one-party systems immediately after independence, Nigeria had a functional, albeit regionally based, multiparty system.

However, the democratic qualities that Nigeria possessed at that time didn’t guarantee the survival of the republic because of certain structural weaknesses and political crises. People ask questions like: what are the factors that led to the collapse of the first republic in Nigeria? Why did Nigeria’s first republic fail? What led to the fall of Nigeria’s first republic? Etc. In this article, answers to these questions will be provided.

Structural Weaknesses that led to the collapse of the first republic in Nigeria

1. Ethnically based Federal Regions, with uneven size and power

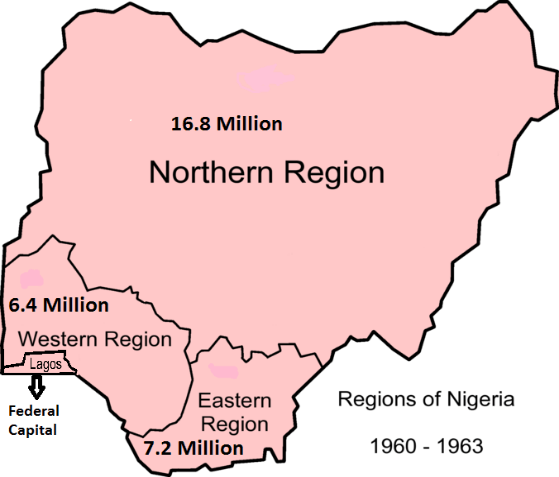

The first structural weakness which set the First Republic in Nigeria for political crisis was its ethnically-based federal regions and the asymmetry in size and power between them. Upon independence, Nigeria was composed of three federating regions: Northern, Eastern and Western regions. (Later in 1963 a new region, the Mid-West, was carved out of the West following a crisis in that region). Each of the regions was dominated by one of the country’s three largest ethnic groups: Hausa-Fulani in the North, Yoruba in the West and Igbo in the East. This arrangement presided over by the dominant ethnic groups placed minorities at a considerable disadvantage in the competition for jobs and resources at the regional level. It also allowed the elites of the three largest ethnic groups to monopolize access to federal patronage, which they leveraged for political support. These three regions were largely autonomous from the federal and were constitutionally powerful as well, a historian of Nigeria’s political parties during this period puts it:

In their respective regions, the leaders of these dominant nationality groups controlled the means of access to wealth and power… They tended to equate their private interests with the objective interests of their nationality groups; conversely, they exploited the sentiments of their groups to promote their private interests.

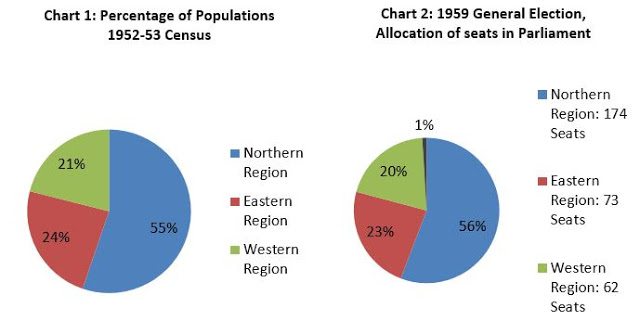

Of the three regions, the North was much larger demographically and geographically (See Fig. 1 & Chart 1). Consequently, it was allocated more than half the seats in the federal parliament (See Chart 2). This meant that a party could potentially govern the country by winning votes from the North alone. This had the double effect of reinforcing the regional outlook of the Hausa-Fulani elites and heightening the fear of northern hegemony amongst Yoruba and Igbo elites.

The country’s federal regions broadly coincided with – and reinforced – the nation’s ethnic cleavages, the exclusion of minorities from each region’s political and economic structures, and the structural tensions which resulted from the Northern region being large enough to dominate its two southern counterparts in parliament, set the scene for the political conflicts which consumed the First Republic.

2. Ethno-Regional Political Parties

The second structural weakness which afflicted the First Republic was the emotive association between political party and ethno-regional identity. This meant politics largely “revolved around ethnic-based regional…parties”. Reflecting the tripodal ethnic balance, three parties bestrode the political scene like titans and thus shaped the destiny of the First Republic: Northern People’s Congress (NPC), the Action Group (AG), and the National Council of Nigerian Citizens (NCNC).

All three parties originally emerged out of ethno-cultural associations:

- NPC from Jam’iyar Mutanen Arewa (Association of Peoples of the North)

- AG from Egbe omo Oduduwa (Society for the Descendants of Oduduwa. In Yoruba folklore Oduduwa is described as the ancestral progenitor of the Yoruba people)

- NCNC from the Igbo State Union

As a result, these three parties and their leaders reflected, shaped, and intensified the nation’s ethno-regional cleavages.

The three dominant parties

The Northern People’s Congress (NPC) was a “Hausa-Fulani dominated party” which held sway in the North. Of the three parties, it was the most entrenched in its regional identity. Nothing illustrates this more than its name, and the fact that in the 1959 eve of independence general election it did not field a single candidate in the other regions.

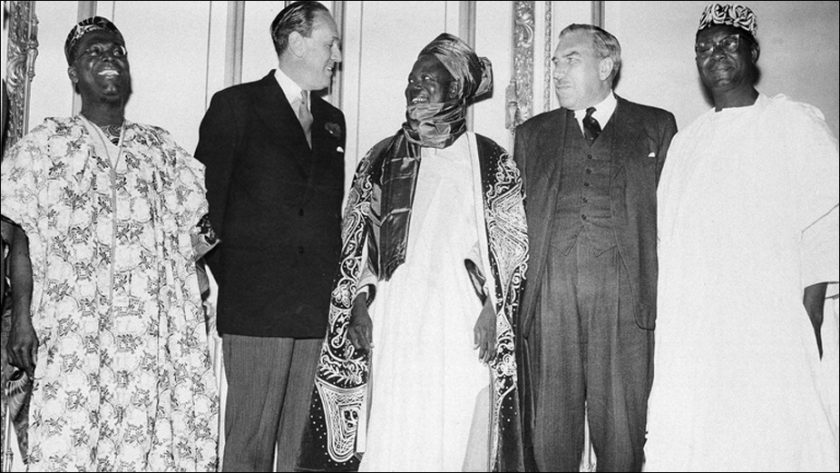

The NPC’s foundational aim was to protect the conservative social hierarchy of the North from the “winds of radical change sweeping up from the south”. The party chairman, who was also the Regional Premier (Premiers were the political leaders of the Regions, analogous to Governors today), was Ahmadu Bello, a titled prince from the region’s aristocracy.

Having won the largest number of seats in the 1959 elections, the party gained the privilege of forming Nigeria’s first post-independence government. However, as it fell just short of winning the majority needed to govern alone (i.e. 157 seats), it had to form a coalition with one of the two main southern parties. Illustrative of the constitutional power of the Regions, Ahmadu Bello, who should have been Prime Minister, being NPC’s party leader, instead chose to remain as Regional Premier, instead preferring to send his deputy, Tafawa Balewa, to Lagos to lead the federal government. This would be analogous to a politician today passing up the opportunity to become President, choosing instead to remain a state Governor.

The National Council of Nigerian Citizens (NCNC) was the southern party which entered into a coalition with the NPC as a junior partner in government. It was a decision for which it was richly rewarded. “Party stalwarts got plum ministerial and ambassadorial posts”. The Presidency (then a largely ceremonial role) for example, which went to Nnamdi Azikiwe, one of the party’s founders, and the Finance ministry went to Festus Okotie-Eboh, the party’s national treasurer.

The NCNC, as its name indicates, originally hoped to project a nationalist, pan-Nigerian image, but the ethnic regionalism which the country’s federal structure encouraged gradually shrivelled the party’s political horizons and it increasingly became the “voice of Igbo nationalism”. Like the NPC, the party’s chairman, Michael Okpara, chose to remain as Regional Premier after the 1959 election rather than take up a seat in the federal cabinet. But unlike the NPC, the NCNC campaigned in the other two regions during the election; it won seats in the West and – in alliance with the Aminu Kano-led Northern Elements Progressive Union – won seats in the North as well.

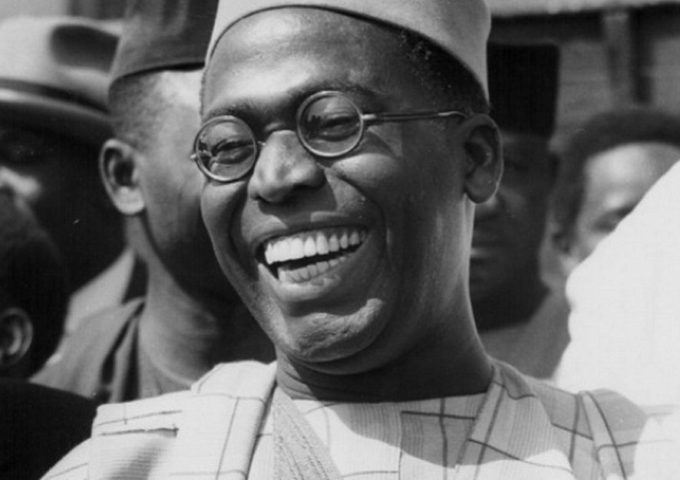

The Action Group (AG) is the last party which completes our tripartite list. The AG, like its southern counterpart, the NCNC, initially aspired to be more than a regional party. It’s advertised political ideology was “democratic socialism” which it hoped would gain it cross-regional support. However, trapped by the nature of the political terrain, party elites soon concluded that “the only certain avenue to power was a regional political party”. Consequently, the AG similarly shrank into its ethnic enclave and never managed to shake off its image as a platform “to safeguard Yoruba interests”.

Like the NCNC in 1959, it also campaigned outside its region and won seats through alliances with ethnic minority parties: United Middle-Belt Congress (UMBC) in the North and Dynamic party in the East.

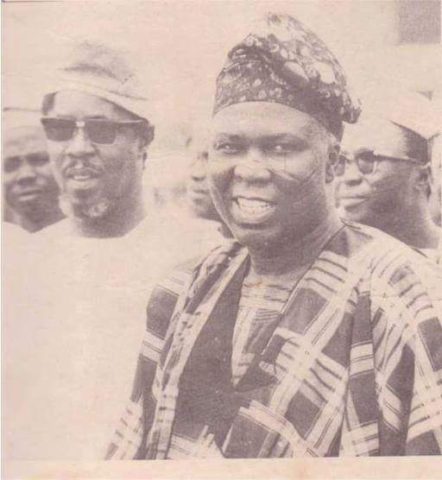

Having won the smallest share of seats among the three major parties, and having similarly performed the poorest in its region (it only won 53% of the seats in the Western Region. NPC won 77% of Northern seats and NCNC won 79% of Eastern seats), the AG thus went into opposition upon independence. Awolowo, the party chairman, became the official leader of the opposition in the federal parliament. He was the only party chairman who “opted to go to the [federal] centre” and leave his deputy, Ladoke Akintola, to become Regional Premier. This decision, however, was to cost Awolowo as it left him “particularly vulnerable” to a leadership challenge from his deputy.

The decision of both southern parties to step out of their ethnic enclaves to field candidates across the federation in 1959 reflected their aspirations that the nation would be an open constituency for all parties to compete in. It was however also a reflection of political reality. Because of the sharp disparity in parliamentary seat allocation, “only the NPC could dominate the federation from its regional base alone”. An advantage neither of the other two parties enjoyed. Consequently, even as the nature of the First Republic’s political culture strongly anchored the AG and the NCNC to their ethnic base, the asymmetry of parliamentary power in the republic necessarily forced them to reach out to minorities beyond their regions.

3. The political alignment which formed after the 1959 election

It can be argued that the political constellation which emerged after the 1959 election was the most potent of the young republic’s structural weaknesses. It had huge impacts on the stability of the soon to be an independent nation. The North-South governing coalition between the NPC and the NCNC, variously described as “unnatural”, a coalition of “strange bedfellows”, only accentuated the republic’s structural imbalances.

On immediate observations, it was certainly a partnership of unequal – with the NPC being by far the more powerful of the two governing parties. This meant the NCNC was always acutely sensitive to the tenuousness of its share of power. Further aggravating the latent tension between the governing duo was the fact that politicians from either party viewed members from the other side with suspicion, condescension, and even hostility. This was a microcosm of the North-South cleavage within wider the Nigerian society just after independence whereby Yorubas and Igbos “sincerely saw the North as feudal and backward, a brake upon nationalist progress”, and the Hausa-Fulanis “sincerely perceived the prospect of Southern domination as a threat to [their] … cultural values”. The deep cultural gulf between the two parties, therefore, led to a governing coalition that was wracked by “tension and mistrust”, such that when multiple crises came the governing alliance repeatedly broke down under the strains.

Thus, another facet of the structural tension caused by the post-1959 political alignment is the misfortune which befell the AG in opposition.

Defeat in the election left the AG “stranded in opposition…without a firm base of power resources”; by extension, it also meant that Yoruba elites lost their bargaining power over the distribution of federal patronage to their region. To illustrate this point: Apparently, part of the “bargain” which the NCNC secured upon joining government was “enhanced entry and promotion for Easterners in the public service and [the] armed forces”. ‘Relegation’ to the status of opposition and loss of access to patronage would eventually split the AG into two camps. The disintegration of the AG into factions was the first crisis which shook the republic early in its life – accentuating all its structural tensions, as we will see in the second section.

4. The fear of ethnic domination

The last and deepest of the structural weaknesses was the fear of ethnic domination which pervaded the politics of the First Republic. The Yorubas and Igbos in the two southern regions feared that the Hausa-Fulanis would use the North’s demographic preponderance to perpetuate northern hegemony and monopolise federal resources for their region; Hausa-Fulanis, in turn, feared that in an open contest, the Yorubas and Igbos, being the more educated, would dominate the political and economic structures of the federation.

Similarly, within the south, the powerful undercurrent of tribalism placed the Yoruba and Igbo elites at loggerheads. And within the three regions, minority ethnic groups lived under the suffocating embrace of the three dominant groups.

Thus, upon independence in 1960, Nigeria had a tense, fractured and conflictual socio-political landscape which resembled what Crawford Young has characterized as a “three-player ethnic game”. This ethnically charged political competition hindered national unity and progress.

Now to the five crises which gradually eroded the foundations of Nigeria’s First Republic, leading to its fall/collapse.

1. The disintegration of the AG, 1962-63

The collapse of the AG’s political power between 1962 and 1963 produced far-reaching effects. The crisis that engulfed the party stemmed from its “staggering defeat” in 1959. It had been ‘relegated’ to the opposition. The NCNC had made impressive inroads into its regional heartland, securing for itself 21 seats in the AG’s political turf by exploiting minority discontent within the Western Region[41]. Most damagingly for Awolowo’s leadership of the party, leading Yoruba personalities interpreted the AG’s opposition role as a defeat for the entire ethnic group.

Under the crushing weight of disappointment, it didn’t take long for the party to fracture. Throughout 1960 and 1961, a simmering tension developed between Awolowo and his deputy, Akintola, who was also the Premier of the Western Region.

The first source of tension was over the ideological orientation of the party. Defeat in the election had led Awolowo to conclude that the AG could revive its fortunes and broaden its support base by sharpening its socialist rhetoric, radicalising its message and stepping up attacks on social inequalities. Awolowo reasoned that such an ideologically radical posture would enable the party to break out of its regional box and draw cross-ethnic support from workers and the underprivileged across the country. This placed him at odds with Akintola and many of the party elites who were regionalist in outlook and status-quo oriented. It also placed him at odds with the “Yoruba businessmen and merchants at the party’s financial core” who worried that Awolowo wanted to take the AG down the route to communism.

Disputes over party strategy further placed Awolowo and Akintola at loggerheads. Awolowo and his faction argued that only a twin strategy of confronting the NPC in parliament, and of luring the NCNC into a “progressive coalition”, could act as a brake on Northern power and therefore secure for Yoruba elites a place at the federal table. Akintola and his faction, on the other hand, countered that moderation toward the NPC – being the dominant party in government – was the best strategy for Yorubas to gain access to the “privileges and benefits in the federation”.

Aggravating the emerging party split was the clash over regional and party control between Awolowo who kept a firm hand in the Western Region to keep his deputy from “wrestling control of the party”, and Akintola who wished to strike out on his own and emerge from under the shadow of his party boss. Akintola was said to have bitterly complained about Awolowo’s “insatiable desire to run the government of which I am head from outside”.

In February 1962, the festering tension finally erupted at the party congress as Awolowo moved to reassert his dominance in the AG. He orchestrated a series of motions which led to “critical changes” in the running of the party. For example, the party constitution was amended to weaken the Regional Premier’s (Akintola) role, and strengthen the party President’s (Awolowo) role in the “Federal Executive Committee” (FEC) – the party’s key decision-making body. In addition, Awolowo’s allies “scored a clean sweep of the elections for major party offices”.

As Akintola licked his wounds, having emerged from the party congress with his pride and power dented, Awolowo moved in for the kill. The opportunity seemed ripe to remove his weakened rival from office. In May, just three months after the party congress, he incited the party into deposing Akintola as Premier and party deputy. Unsurprisingly Akintola refused to go down quietly. He challenged the constitutionality of his removal in court, “vowing a fight to the finish”.

By now the disintegrating AG and the deepening split in Yoruba elite cohesion was clearly becoming a “threat to peace and order in the West”. Violent riots erupted throughout the region as the power struggle between the two men and their factions spilt out into the streets. The NPC and NCNC watched the deepening fragmentation of their Western rival with cautious optimism. They believed that the intra-party conflict would open up the West, allowing them to extend their influence into the region. Ahmadu Bello, the NPC party chairman and Premier of the North went as far as issuing a public statement of support for the embattled Akintola.

The struggle between the two factions reached its climax on the 25th of May when the Awolowo faction attempted to vote in a new Regional Premier, Alhaji Adegbenro, in the regional parliament. The parliamentary procedure descended into physical violence. Calculating that in any vote they would lose as they were in the minority, parliamentarians from the Akintola faction, supported by NCNC members of the Western regional assembly, resorted to violent disruption to block Adegbenro from being sworn in.

John Mackintosh, a British political scientist, then lecturing at the University of Ibadan, described the scene in parliament:

The House of Assembly met at 9 a.m. and after prayers, as Chief Odebiyi rose to move the first motion, Mr E. O. Oke, a supporter of Chief Akintola, jumped on the table shouting ‘There is fire on the mountain’. He proceeded to fling chairs about the chamber. Mr E. Ebubedike, also a supporter of Chief Akintola, seized the mace, attempted to club the speaker with it but missed and broke the mace on the table. The supporters of Alhaji Adegbenro sat quiet as they had been instructed to do, with the exception of one member who was hit with a chair and retaliated. Mr Akinyemi (NCNC) and Messrs Adigun and Adeniya (pro-Akintola) continued to throw chairs, the opposition joined in and there was such disorder that the Nigerian police released tear gas and cleared the House.

The Prime Minister, Sir Tafawa Balewa, gave an even more graphic account of events:

The whole House was shattered, every bit of furniture there was broken … some persons were stabbed

As the AG reeled from this assault, the two governing parties stepped-up the offensive by instituting a commission of inquiry in June – “the Coker Commission” – to investigate allegations of misuse of public funds in the Western Region. The Commission found Awolowo guilty of embezzling millions in cash and over-draft from government companies and parastatals, and of “trying to build a financial empire through abuse of his official position”. Such was the drain on regional funds by Awolowo and AG party stalwarts that by 1962 the Western Region Marketing Board – the wealthiest of the three regional marketing boards – “had to borrow to perform its own routine operations”.

While there was “little surprise or shock among AG supporters” at the extent of the fraud uncovered, and while few doubted Awolowo’s pivotal role in the scandal, many however felt that the findings of the Commission were selective and driven by a political agenda. For a start, its complete exoneration of Akintola from any of the financial misdemeanours struck many as absurd as he was the party deputy and Regional Premier while the region’s funds were being siphoned off to fund party activities. Also, most observers felt that had a similar investigation been done over the finances in the other two regions, the same level of abuse of public funds would have been uncovered.

With Coker Commission’s revelations inflicting damaging blows on Awolowo and the AG’s prestige, the Emergency Administrator’s restrictions on AG members were gradually relaxed for Akintola’s supporters and that for Awolowo’s tightened[65]. This allowed Akintola to regroup his supporters; setting the stage for his eventual return as Premier.

Under the unrelenting pressure, many Awolowo supporters defected to Akintola’s side in a bid to save their political careers. As indications multiplied that Akintola, backed by federal might, would be reinstalled as Regional Premier without a re-election after the Emergency period expired, some Awolowo supporters began secretly plotting the government’s overthrow. The plot, however, was uncovered by a police informant.

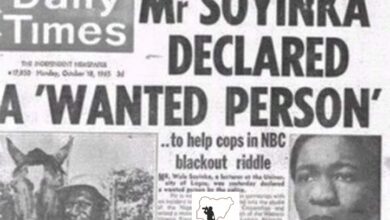

In September 1962, the Prime Minister “revealed to a stunned nation” the uncovered plot. In November, Awolowo and the decimated leadership of the AG, now languishing in prison, were charged with “treasonable felony” and “conspiracy to stage a coup d’état”. In December, the NPC-NCNC federal government announced that it would no longer recognise the party as the official opposition.

1963 brought no respite for the rapidly collapsing AG. On the 1st of January, to the surprise of few, Akintola was re-installed as Regional Premier without an election. An election would have revived the flagging fortunes of the AG as Alhaji Adgbenro, the party candidate, would almost certainly have won. Akintola’s return was only made possible by his alliance with one of the governing duo – the NCNC. In return, Akintola rewarded his Eastern ally with a “generous share of power in the West”, resulting in the NCNC scooping up numerous regional ministerial portfolios. More seriously for the Yorubas, particularly in view of the ethno-regional balance-of-power, Akintola was forced, as part of the bargain, to accept the partition of the West. This would eventually lead to the creation in August of a new region – the Mid-West – for the minorities in the West.

All the regions had their minority troubles. In the East, for example, the Ibibios, Efiks and Ijaws, to name but a few, all harboured separatist sentiments against their domineering Igbo overlords. And in the North “escalating political repression” twice plunged the region’s Tiv areas into open rebellion, in 1960 and 1964.

After the partition, and with its destruction nearing completion, two events finally finished off the AG as a credible force on the national scene.

The formal publication of the Coker Commission report in January 1963 gave the NPC-NCNC-led federal government and the Akintola-led Western Regional government the legal cover they needed to confiscate the assets of the AG, and break up its “commercial and financial” networks – steps which did “real damage” to the party. And on September 11, Awolowo and his co-conspirators were finally found guilty of the treasonable felony charge and sentenced to 10 years in prison. This effectively wiped out the top echelons of the AG.

The eminent Stanford political scientist, Larry Diamond, in his Class, Ethnicity and Democracy in Nigeria, described the collapse of the AG thus:

The breadth and magnitude of the defeat inflicted upon Chief Awolowo and his AG supporters by the NPC and the NCNC was simply staggering. Not only did the Awolowo Action Group lose the power struggle in the West, it was also…destroyed…as an effective opposition force

The collapse of the AG immediately led to realignments in the political constellation. With his regional rival in jail and his grip over the West consolidated, Akintola shook off his alliance with the NCNC, dismissed their members from the regional cabinet, formed a new party – the Nigerian National Democratic Party (NNDP) – and realigned it with the NPC. This was arguably where he had always wanted to be, as close as possible to federal power. He probably calculated that under the nourishing embrace of the dominant party in government, he could rebuild the shattered position of the West and restore the Yorubas to parity in the ethno-regional balance. More fundamentally, the collapse of one pole (the AG) transformed the contest from a tripolar struggle to a bipolar one. With the disappearance of the AG as a national political force, the two governing parties now faced each other in direct and increasingly acrimonious confrontations. Like the breaking of the ground after an earthquake, deep fissures opened between the NPC and the NCNC.

As the dust settled from the crisis, it became manifestly clear that the NPC had reaped the biggest windfall. With a dependent ally in Akintola’s NNDP now in control of the Western Region, the southern dream of an east-west ‘progressive alliance’ against Northern hegemony was shattered. And with 16 independent parliamentarians having earlier in 1961 joined the NPC, their party now had a slim working majority in parliament. These developments meant the NCNC effectively lost its leverage over the federal government, and therefore its “extractive capacity” – denting its power and confidence.

The Northern Region now stood poised to bring Nigeria under its sole captaincy. John Stuart Mill, in his 1861 Considerations on Representative Government, set out several conditions for a stable federation, one of which was that “there should not be anyone State [or Region] so much more powerful than the rest as to be capable of vying in strength with many of them combined. If there be such a one … it will insist on being master of the joint deliberations”.

Eastern Regional Premier, Michael Okpara, belatedly recognizing that the emerging political balance would be unfavourable to the East, tried to “drawback” from the “total extinction” of the AG. Maitama Sule, then an NPC Federal Minister, however, observing the changes taking place, remarked with breath-taking confidence: “In a very short time, the NPC will rule the whole of Nigeria”.

It was against this background that the First Republic’s next crisis played out.

2. Census Crisis, 1962-64

In May 1962, as the AG crisis was reaching its peak, the nation prepared for its first census as an independent country. The last census, which had been conducted in 1952-53 under the auspices of the British, had been the basis for the distribution of parliamentary seats prior to the 1959 election. Northern power, and the NPC’s dominance, largely resulted from this census. Consequently, when a new census became due in 1962, implications for the ethno-regional balance-of-power inevitably shaped its meaning.

Yoruba and Igbo elites, in particular, viewed the census as an opportunity to change the unfavourable situation by reducing the demographic gap between the North and the South. They reasoned that if the population count could be turned in favour of the South, power relations between the three regions would equalize and the “basis of Northern domination would be permanently removed”. The census would also determine the revenue allocation formula going forward, and the quota for recruitment into state structures, such as the Armed Forces and the Federal Civil Service. Given such stakes, it wasn’t surprising that the census generated an atmosphere of “feverish competition” as ethnic champions mobilised their constituencies for the coming contest. In the South, for example, Diamond states that:

Politicians were touring their constituencies urging the people ‘not to be left out’. It was suggested that besides the distribution of seats, amenities and scholarships would be shared on a popular basis, so…there was every advantage in obtaining ‘a good result’. Politicians and ethnic-group leaders were ‘out to win’ and ‘their campaign was only too successful’.

Expectations of a ‘good result’ in the South were also heightened by the fact that many southerners believed that the 1952-53 census, which had been conducted by the colonial authorities, were “grossly inaccurate…and deliberately falsified by the British to ensure Northern dominance”. There remains a widespread belief that British colonial officers were “naturally inclined towards the North”. Adding to the south’s positive expectations was also the belief that with generally better health care than the North, and a more “rapid decline in infant mortality”, the southern regions combined could expect better population numbers.

The counting of the census took place over two weeks in early May 1962. As the figures came in, it became immediately evident that some implausible increases had occurred between the last census and this. While the North’s increase of about 33% broadly tallied with the UN’s demographic projections. The East and West had scored staggering increases of 72% and 70% respectively. Some areas in the Eastern Region, for example, were posting increases of between 120% and 200%. With such astounding increases, it was either the southern regions had broken all known records of human reproduction, or else “statistical surgery” had taken place. The chief census officer opted for the latter explanation. Commenting on the particularly unbelievable figures coming in from the Eastern Region, he stated:

In the five Eastern divisions which had shown increases of over 120 per cent in ten years, several checks could be applied … [Most] telling, the biggest increase was in children under the age of five, and calculations showed that the women of child-bearing age could not have produced this number of births had they all been pregnant for all of the five previous years.

The report of the chief census officer submitted to government confirmed the massive population inflation that had attended the process and proposed verifications be carried out in certain areas to rescue the credibility of the census. As the government prepared for the verification checks, it imposed a veil of secrecy on the fraudulent census result to quell potential riots over the new figures.

Casting aside the secrecy, Michael Okpara broke ranks and announced that the Eastern Region now had 12.4 million people as per the census, and insisted that his Regional government would be sticking to this figure regardless of the conclusions of any verification exercise. Verification checks and recounts went ahead nonetheless, and northern leaders promptly restored the balance by “discovering” an extra 8.5 million northerners.

This brought the north’s population to a new total of 31 million, up from the 22.5 million in the initial count – comfortably large enough to maintain its preponderant advantage. The NCNC led the south in completely rejecting the results of the verification exercise. The governing alliance broke down as the NCNC pushed for the release of the original census result, while the NPC backed the authenticity of the verification checks. Given this impasse, the 1962 results were cancelled and a fresh census was announced for the second half of 1963.

The 1963 census turned out to be an even greater debacle. The political stakes attached to this new census were even more pronounced. With the 1964 general election just under a year away, and with the heightened insecurity felt in the south over the NPC’s growing power, ethnic political security took centre stage. In the Eastern and Western Regions, ethnic champions once more mobilized their constituencies to deliver a ‘good result’. Restraints from the first-time round were abandoned. In the North, having been latecomers to the inflation game in 1962, regional leaders there were determined not to be caught napping in the 1963 rerun. Eastern inspectors on their way to verify Northern numbers, for example, reportedly had their trains derailed. Livestock was apparently counted in some places as part of the human population. And “travellers and passers-by” were counted as part of the settled population. Double counting took place in all the four regions (by now the Mid-Western Region had been created).

Once again, amidst bitter recriminations that each region had massively inflated their numbers, the government refused to immediately release the results of the 1963 census. While the official figures for the ‘63 census were never released, reports quickly circulated however that the figures had totalled up to an incredible 60.5 million – meaning an extra 15 million Nigerians had been added unto the total of the notoriously inflated 1962 census. While publicly the government pleaded for time so it could carry out “exhaustive tests” on the data it had received, privately ethnic elites from all the regions were engaged in hard bargaining to secure the best numbers for their constituencies.

On the 24th of February 1964, the result of the compromise was announced to the public: there were to be 55.6 million Nigerians – 10 million larger than the notorious figures of 1962. The East kept its 12.4 million figures from the 1962 count; the North reduced the 8.5 million Northerners it had ‘discovered’ to a more respectable 7.3 million, bringing its total population to 29.8 million; the West added an extra 2.5 million to its 1962 figures, bringing its population to 10.3 million; the Mid-West was allowed to inflate its numbers by 300,000, to bring its population to 2.5 million; and a population of 665,000 was ‘counted’ for Lagos. The North had kept its comfortable demographic preponderance.

Not even this compromise was enough to calm frayed nerves as tensions erupted once more within the governing alliance. The NCNC accused the NPC of unilaterally releasing the figures before consultations were finished and final agreements reached. Consequently, Michael Okpara in the East rejected the February 1964 figures as “worse than useless”. Dennis Osadebay, the Mid-West’s Premier and an NCNC member, echoing his Eastern ally, similarly condemned the figures as “the most stupendous joke of our age”. Akintola in the West, being dependent on the NPC for his position as Regional Premier accepted the results.

As the NCNC manoeuvred to get the 1963 results cancelled, the NPC, using its control of the Federal Government, forced Osadebay into abandoning his Eastern ally and toeing the government line by threatening the Mid-West with withdrawal of federal aid – a move which would have financially crippled the new region. With the NCNC consensus broken and the Eastern Region isolated, Michael Okpara too was eventually forced to accept the new figures. The imbalance of power was now more acute than ever before.

As the nation breathed a sigh of relief at having survived another crisis which had severely strained the unity and stability of the republic, all attention focused on the next big event less than ten months away: the 1964 general election. Southern elites looked to the election as the one last chance to break the NPC’s momentum. Among northern elites, however, there was the general expectation that the election would reproduce their federal dominance. As the parliamentary secretary of the Northern House of Assembly, Alhaji Kokori Abdul, said just a couple of months before the election:

I have no doubt whatever (sic) … that the Northern People’s Congress has come to stay and to continue to stay and is going to rule Nigeria forever.

With the reverberations from the previous two crises deepening the cracks within the system, it should have been evident to the nation’s leaders that the First Republic could not withstand another political crisis. And sure enough, the upheavals unleashed in 1964 and 1965 eventually led to the republic’s catastrophic end in 1966.

3. The General Strike, June 1-13, 1964

To all intents and purposes, by 1964, the First Republic stood at a critical juncture in its political life. Its birth pangs had been accompanied by political instability caused by the nation’s elites jockeying for state power. With the census crisis finally winding down at the beginning of the year, all energies were soon concentrated on the forthcoming general election to be held on the 30th of December. While the collapse of the AG as a national political force had opened deep cracks within the ruling coalition, the long-running census crisis had progressively hardened the dividing line between the NPC and the NCNC. The general strike would finally shatter the fragile governing alliance.

On the 1st of June, after about a year of brinkmanship between the government and state employees over the issue of a living wage for workers, the country’s labour unions united under the banner of a Joint Action Committee (JAC) and declared a general strike. For thirteen days, economic activity was paralysed and “essential services [brought] to a virtual standstill” as about 750,000 of the nation’s estimated one million wage labourers downed tools and refused to work. Of the 750,000 strikers, only about 300,000 were part of the labour unions that had called the strike, an indication of the strike’s mass support.

After a week of protests and strike action, the government entered talks with the JAC. On the 9th of June however, the talks broke down in stalemate. In defiance, the JAC demanded the Prime Minister return to the negotiating table or “resign within 48 hours”. NCNC leaders, calculating that the tidal wave of discontent unleashed by the strike action could be turned into an electoral advantage, abandoned the government line and openly sided with the striking workers. The NCNC’s open support of the JAC all but permanently broke the governing alliance.

With the strikers gaining in confidence and expanding their support base, the government (by this time it was effectively the NPC alone) finally buckled under the pressure and gave in to the demands for salary increases on the 13th – ending the 13-day strike. As an indication of how volatile the situation had become, Howard Wolpe, in his Urban Politics in Nigeria, advances the argument that, aside from the desertion of the NCNC and the growing dangers of a wider social revolt, another factor which forced the NPC’s hand was the threat of a “local police uprising in Lagos” in support of the striking workers.

On the surface, the strike was the result of workers’ demand for a new minimum wage in the private and public sectors. On a deeper level, however, it was also a reflection of the dissatisfaction and discontent within the wider populace against corruption, widening economic inequality, and the seeming failure of the political elites to deliver the dividends of independence. By 1964, endemic corruption, ministerial profligacy, and the corrosive effects of ethnic politics had seriously eroded the First Republic’s legitimacy. The “spreading virus of corruption and the enormous salaries at the bloated higher ranks of government” placed great strains on any “domestic capital that could be mobilised” for investment. Bribes for government contract were rampant. The privileged flaunted their illegally acquired wealth, crystallizing the general sense of moral decay and social injustice.

No one exemplified the First Republic’s problem with endemic corruption more than the Finance minister himself, Festus Okotie-Eboh. Such was his notoriety that a foreign official reportedly gave this witheringly unflattering portrait of him:

Chief Festus Okotie-Eboh was a fat, jovial character … [whose] name had become synonymous with corruption in Lagos… [He] was a squalid crook who dragged Nigeria down to his level… He dragged Nigeria into the sewer, but because of his corruption, Nigeria has no sewers. The money to pay for them is still in Swiss banks.

Diamond, in his penetrating assessment of the general strike, commented that:

More than just a strike by the nation’s workers for higher wages … it was a sweeping challenge to the entire political class and its ruling authority … [and] … over the entire structure of inequality in Nigerian society. Union leaders fixed their protest … on the glaring levels of corruption and extravagant consumption by the nation’s political elite. It was this larger issue that rallied the broad-based and spontaneous outpouring of popular support for the strike in most Nigerian cities.

4. The General Election, December 1964

Just as the mass popular appeal of the strike seemed to foreshadow a new dividing line hardening along class lines, a deeper, more fundamental, cleavage reasserted itself. Out on the campaign trail, the elites, to lock in their vote share, amplified their appeals to ethnic identity in ways that strained the fragile national bond.

In the Western Region, for example, Akintola constantly stoked fears of Igbo domination to shore up the sagging support of his unpopular party, the NNDP. With Yoruba elites stuck in the wilderness of opposition, he argued, Igbo leaders had used their access to federal patronage to muscle their ethnic kinsmen into senior government posts to the detriment of the Yoruba nation. As he put it:

Notwithstanding our wealth and high social advancement, Western Nigeria has become a mere appendage in the community of the Federal Republic of Nigeria … and as a result they have been superseded by relatives, tribesmen and clansmen of the eastern NCNC chairman, who shout the slogan of one Nigeria more than anyone else.

Igbo leaders responded by calling on their ethnic kin to “rally to the defence of their embattled people” by voting for the NCNC. While AG leaders, not to be outdone by their rivals, moved to lock in northern minority votes by promising to “end … Hausa-Fulani domination”.

The political environment was made more volatile by the shift in party alignments taking place. The NPC-NCNC confrontations over the previous years, and the final collapse of the governing coalition after the June general strike exerted a powerful gravitational pull on the political space. This led to the emergence of two opposing alliances for the coming election: Nigerian National Alliance (NNA) led by the NPC and comprising Akintola’s NNDP and other minority parties from the South, and the United Progressive Grand Alliance (UPGA) led by the NCNC and comprising the AG and other smaller parties from the north.

Despite this seemingly national coalition, the two opposing alliances essentially represented a “North-South constellation of forces”. The pivotal core of the NNA was the NPC. Its alliance with ethnic minority parties beyond its region stemmed from the realisation on the part of the Hausa-Fulani elites that though hegemony in the Northern Region could deliver the Nigerian state to them, extending their power into the Southern regions by proxy would allow them to better consolidate their federal dominance. Similarly, while the central pillar of the UPGA was the NCNC, the acute fear of growing NPC power drove the NCNC’s strategy of reaching out to minorities and radicals in the northern region. For UPGA party bosses, this was a matter of ethnic political security. Simple arithmetic dictated that only by penetrating the north could they hope to, at the very least, block the NPC from gaining full control of the state.

Adding an extra layer of complexity and tension was the breakdown in Yoruba elite cohesion; a ripple effect of the Awolowo-Akintola power struggle. The shattered remnants of AG, now led by Alhaji Adegbenro, saw the election as a chance to re-establish the party’s control of the Western Region. The party, like most Yorubas, amongst whom it was still very popular, also concluded that full NPC control of Nigeria was dangerous to the interests of the Yoruba nation, hence its decision to join the UPGA coalition. The NNDP on the other hand, owing to its dependence on the NPC for its rule in the Western Region, and owing to Akintola’s belief that only an alliance with the NPC could secure the long-term interests of the Yorubas, unsurprisingly joined the NNA coalition. Akintola also saw the election as a chance to finish off the AG once and for all and establish his hegemony in the Western Region.

The electoral campaigns of both coalitions were marked by violence and strong-arm tactics. Thugs were freely recruited to intimidate opposition supporters. Political opponents were beaten up. The NPC especially, fully used its incumbency advantage – jailing opposition candidates or supporters for the slightest infractions. In strategic areas where the stakes were too high, both coalitions sometimes reportedly resorted to the “physical elimination of opposition candidates”. The desperate appeal of the Inspector General of Police to the supporters of the contending parties illustrates the thuggery and hooliganism which characterised the run-up to the election:

Don’t arm yourselves with broken bottles, hatchets, sticks… Do not set fire to the motor vehicles of your political opponents.

With the situation seemingly escalating beyond control, there were the first “rumblings of a possible military coup” within the army. Disturbed by the unfolding events, Nnamdi Azikiwe, the Federal President, confided to an interviewer on his 60th birthday in November that “what is happening in Nigeria today does not inspire me to be optimistic that we shall survive as a nation”. He followed this with a dramatic dawn broadcast on the 10th of December warning that the unity of the nation was at risk:

I have only one request from our politicians … If this embryo Republic must disintegrate, then, in the name of God, let the operation be a short and painless one… And I have one advice to give our politicians: if they have decided to destroy our national unity, then they should summon a round-table conference to decide how our national assets should be divided before they seal their doom by satisfying their lust for office… It is better for us and for our many admirers abroad that we should disintegrate in peace and not in pieces.

Unfortunately, not even such a solemn intervention could stem the growing tide of violence and lawlessness. Prime Minister Tafawa Balewa, supported by the Northern and Western Premiers – Ahmadu Bello and Akintola respectively – dismissed the accusations of electoral malpractices as “unjust” and “groundless”. Given their party’s incumbency advantage at the federal level, they were supremely confident of out-rigging their UPGA rivals in the forthcoming election. With the determination of the NNA to hold the election unswayed by unfolding events, half of the members of the Federal Election Commission resigned in protest. UPGA leaders, frustrated by their inability to match the NNA’s disruptive tactics, decided to boycott the election. It turned out to be a hasty and unwise decision.

The elections went ahead as scheduled on the 30th of December. The UPGA’s absence left the field wide open for NNA candidates to sweep all before them. In the Northern region, the NPC won 162 seats of the 167 seats in that region. Should the results stand, the NPC could now govern the Federation alone – 157 seats were what was needed to form a majority in the Federal Parliament.

In the Eastern Region, the NCNC was able to block any voting from taking place. While in the Western and Mid-West Regions, recognising it had seriously blundered, and alarmed at the prospect of being completely obliterated from the political map, UPGA leaders called off the boycott and sent out their candidates to contest. The call-off came too late to reverse the tide against the party. In the Western Region, in particular, the “electoral process was so abused” that though intensely unpopular, the NNDP won a scarcely believable 63% of the seats in that region (It won 36 seats out of 57 seats allocated to the region: see Table 2). UPGA leaders immediately rejected the results and called for new elections to be held.

With the NNA coalition having secured a historic ‘victory’ at the polls, Tafawa Balewa called on the President to reappoint him as Prime Minister. Sharply critical of the “conduct and outcome” of the election, on January 1, 1965, Azikiwe refused; instead, informing Balewa that the elections were “unsatisfactory in view of the violations of freedom of recent weeks”, he threatened to resign if the results were not scrapped and new elections called. For four days, the First Republic “teetered on the edge of an abyss” without a government as both Azikiwe and Tafawa Balewa competed “for control and support of the armed forces”. There were calls for Azikiwe to assume executive powers and nominate a Prime Minister of his choice, and Balewa confided to the Chief Justice his intention to nominate a new President to succeed Azikiwe. Secessionist rhetoric grew louder and the dangers of a civil war loomed larger.

With legal advice from the nation’s senior judges strongly indicating that in the event of conflicting orders the armed forces were legally obligated to obey the Prime Minister alone, and with rumours circulating that the Prime Minister was reportedly planning to orchestrate his removal by “having him declared medically incapacitated”, the President finally relented on the 4th of January. Under the so-called “Zik-Balewa pact”, Azikiwe agreed to invite Balewa to form a new government in return for Balewa agreeing to the following conditions: (1) form a “broad-based government” with members of the opposition incorporated into the cabinet; (2) reschedule the boycotted elections in the Eastern Region for March; and (3) hold new elections for the Western Region’s House of Assembly in October to choose a new Premier for the Region.

The rescheduled election took place in the Eastern Region without incident. The NCNC, appealing to Igbo unity, easily secured 91% of the seats in that Region. As per the arrangement reached in the ‘Pact’, many newly elected NCNC members were absorbed into the federal government, bringing the federal cabinet to the “unprecedented size of eighty ministers”. Commenting on this development, Falola, in his The History of Nigeria, remarks with biting sarcasm: “The government had now been converted into a holding company with every ‘big politician’ becoming a shareholder”.

5. The Western Regional Election, October 1965

The disaster of the 1964 election, unfortunately, failed to act as a salutary check on the “win-at-all-costs mentality” of the nation’s leaders.

A rerun of the Western regional election was one of the main pillars of the Zik-Balewa pact. The NCNC had insisted that an election be held to choose a new Premier in the region as a precondition for accepting the results of the 1964 election. They were confident that in a free and fair election, their Western ally, the AG, would be able to dislodge the NNDP from the region – with Alhaji Adegbenro replacing Akintola as Premier. Their hopes were quickly dashed. Akintola was not ready to relinquish power without a bruising fight.

Two factors combined to ensure that the fraud and violence which characterised the 1965 Western election surpassed the general election in 1964. First was the fact that unlike the other three regions – Northern, Eastern and Mid-Western – which were effectively “one-party states”, in the West, intra-elite conflict meant two parties (AG and NNDP) representing the contending elite factions were “engaged in a deadly rivalry” for political survival. To quote Diamond:

If Chief Akintola’s ruling party, the Nigerian National Democratic Party (NNDP), won a full five-year term, Action Group leaders knew it would continue to use regional power ruthlessly to extinguish their party. The Akintola forces, on the other hand, expected, in the case of defeat, to become the victims of their own methods, without a genuine base of popular support to sustain them.

The second factor was the fact that though the election was on the surface a Western regional affair, the outcome was, however, of “critical importance … to the game plans” of leaders in the Northern and Eastern Regions. A pliant ally in the West would allow the NPC to consolidate its hold on the federal government. For the NCNC on the other hand, a revived and strong AG, in alliance with it, would provide the needed counterweight to forestall impending NPC hegemony.

Akintola, acutely aware of his weak hand, resorted to ethnic mobilisation to shore-up his support. He beamed his searchlight on public institutions in the region were Igbos held senior positions and led the calls for their dismissal. One such institution was the University of Lagos, where the Vice-Chancellor was forced out and replaced by a Yoruba man. However, knowing that the rhetoric of ethnic chauvinism on its own would not be sufficient to dent the AG’s chances of winning, Akintola also used his incumbency advantage to full effect: blocking AG candidates from campaigning and intimidating their supporters from holding rallies. There was no doubt within the NNDP camp that only “wholesale electoral fraud” could rescue them from humiliating defeat at the polls.

When the election itself came, very few were surprised by the riggings that took place. But what angered many, and perhaps contributed to the orgy of violence that followed the election, was the sheer brazenness and impunity with which the NNDP went about the business of rigging its members back to parliament. For example, rather than bother with the logistical inconvenience of inflating disagreeable figures that had been announced at polling stations, the NNDP simply had many of its newly ‘elected’ parliamentarians declared “unopposed” winners in radio stations. The Chairman of the Electoral Commission resigned in protest, declaring he “had no confidence in the conduct of the elections”.

Disregarding the brazenly fraudulent results being announced on the radio, the AG announced itself the true winner of the election and tried to swear Adegbenro as the Premier – leading to his arrest for “illegal assumption of office”. AG supporters poured into the streets. The spasm of violence which engulfed the entire Western region was unprecedented. There was widespread destruction of life and property. Political thugs took to setting fire to persons – especially targeting NNDP supporters and Hausa-Fulani settlers – and properties in what they called Operation Wetie, meaning to “wet with petrol and burn”.

As the Western Region slid into anarchy, the Prime Minister refused to impose a State of Emergency in the region, as he had done in 1962 during the AG crisis – or at the very least call in the army to restore order. Some have since argued that Tafawa Balewa refused to declare a State of Emergency because his party was allied to the NNDP, and therefore didn’t want to throw it out of power so soon after its ‘election’. Others have similarly argued that his refusal to call in the army was influenced by his belief that many of the soldiers stationed in the region were sympathetic to the opposition’s cause. Others still have suggested that the government was indecisive because it was “waiting for the crisis to escalate to a point that would justify the use of the armed forces as an army of occupation in the Western Region”.

In any case, the 1965 October ‘election’, and the spasm of violence which accompanied it, turned out to be the last act in Nigeria’s First Republic’s tragic political drama. As Diamond argues:

If [the] various social elements had any faith left in the institutions of the First Republic, it was irrevocably shattered by the 1965 ‘election’ in the West, which seemed to obliterate any remaining vestige of the Republic’s democratic character.

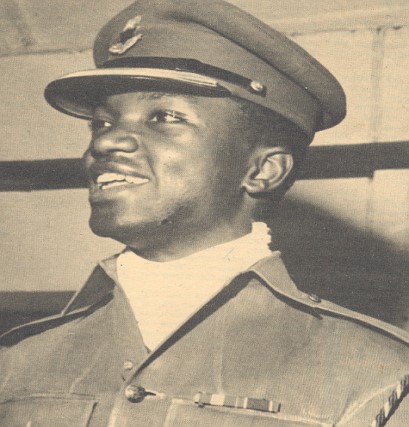

On the 15th of January 1966, elements within the army, hoping to lead a military revolution, struck with lethal force and wiped out the top tiers of the Republic. On the 16th of January, the army chief took over as Head of State, formally ending the First Republic. By the 17th of January, when the last of the mutineers had surrendered to the new military government, the Prime Minister (Tafawa Balewa), Finance Minister (Okotie-Eboh), Premiers of the Northern (Ahmadu Bello) and Western (Akintola) Regions, and seven senior military officers, had all been gunned down.

The bloody coup of 15 January 1966 that was led by Kaduna Nzeogwu brought to an ignominious end a democratic Republic that had begun with much promise.

References:

- Akin Alao. (2015), ‘The Republican Constitution of 1963: The Supreme Court and Federalism in Nigeria’, University of Miami International and Comparative Law Review,

- Anglin, D. G. (1965), ‘Brinkmanship in Nigeria: The Federal Elections of 1964-1965’, International Journal, Vol. 20, No. 2: pp. 173-188.

- Operation Wetie And The 1962 Action Group Crises: How Power Tussle Between Awolowo And Akintola Plunged Western Region Into Crises; Teslim Opemipo Omipidan – OldNaija

- Jackson, L. R. (1972), ‘Nigeria: The Politics of the First Republic’, Journal of Black Studies, Vol. 2, No. 3: pp. 277-302.

- Janguz Arewa – The Fall Of The First Republic

- Ohinmore, O. M. and Vaaseh, G. A. (2011), ‘Ethnic Politics and Conflicts in Nigeria’s First Republic: The Misuse of Native Administrative Police Forces (NAPFS) and the Tiv Riots of Central Nigeria, 1960-1964’, Canadian Social Science, Vol. 7, No. 3: pp. 214-222.

- Siollun, M. (2009), Oil, Politics and Violence in Nigeria: Nigeria’s Military Coup Culture 1966-1976. New York: Algora Publishing.

- Countries Studies – The First Republic

Questions? Advert? Click here to email us.